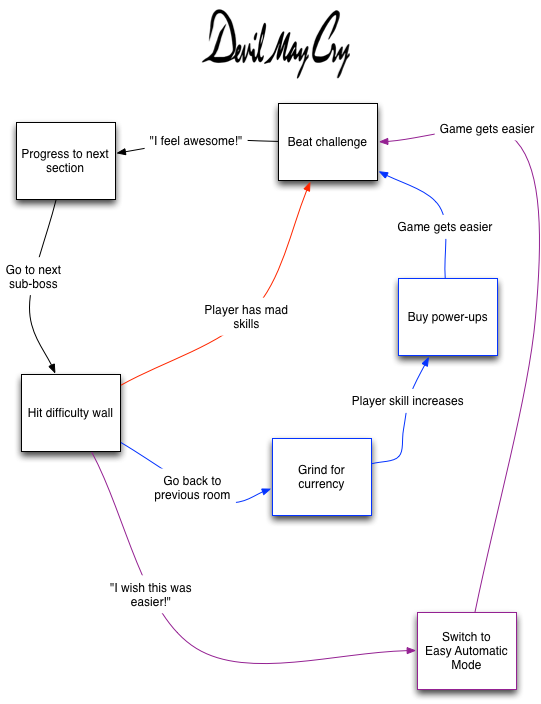

The first 20 minutes of Devil May Cry are really clever. What happens is this: you breeze through several rooms, chopping evil marionettes left and right and flicking that silver hair around like you own the world. After the second or third room the game offers you the option to switch to “Easy Automatic Mode,” in which the game becomes easier. It’s pretty easy at that point, so you probably ignore the offer. But a few minutes later Devil May Cry throws you at the first boss (a giant lava spider) and you die. I mean, you die. You get your butt handed to you on a platter. The giant lava spider is way, way tougher than anything you’ve seen in the game so far. It’s not even clear how to damage the thing at first. You get beat down, hard. You try again, but it’s futile. The lava spider is too difficult. At this point you have four options:

- Quit playing,

- Turn on Easy Automatic Mode and try again,

- Step up and become much more skilled to beat the boss, or

- Figure out that you can go back and keep killing marionettes to grind for items which you can then use in a shop to power yourself up to make the boss more reasonable.

This is a genius little bit of manipulation because what the game is really doing is forcing you to identify, early on, the kind of experience you want. If you quit, well, you probably do not have the patience required to enjoy the rest of this game. If you turn on Easy Automatic Mode, you’ve identified yourself as somebody who wants to play but isn’t interested in a pride challenge. If you skill up, you’re a hardcore mofo and the game should throw everything it’s got at you. The last option, the one that I think most players choose, is to go back and grind.

But grinding serves a purpose. It forces you to learn about second- and third-order game systems, like controlling your combos to increase the number of style points you get. It is here that you unlock the real meat of the game design: you’re not just supposed to button mash through dudes, you’re supposed to control your combos to destroy the opposition as stylishly as possible. Doing so increases your style score, which increases the payout of each felled enemy, which lets you upgrade to become even more badass. This is a much more interesting (and difficult) challenge, and adds a lot of depth to the moment-to-moment gameplay. Devil May Cry uses its first boss as a forcing function to figure out what kind of player you are, and it compels you to unwittingly select a play style that you prefer.

Why does it do this? Because the rest of the game is even harder than that lava spider boss, and becoming skilled enough to make progress requires that you be really invested in the core game mechanic. Button mashing isn’t enough to sustain most players’ interest through the incredibly demanding difficulty curve that Devil May Cry employs, but by tricking you into learning about the extra depth in the combo system, the game is actually ramping you up for a more interesting experience.

It’s really quite manipulative if you think about it. The system is designed to carry the maximum number of people through the level content, and hopefully make them feel good about it. It’s a carefully constructed trick, aimed right at the psychology of the player who feels that he has something to prove. Going a step further, we might even see the offer to switch to Easy Automatic Mode as a challenge: “hey, if you can’t take the heat, there’s always training-wheels mode over here.” Players who aren’t putting their pride on the line will see Easy Automatic Mode as a welcome way to reduce frustration. Players who want bragging rights for their skills see it as a personal insult. The game uses this form of manipulation to ensure that both types of players are put on a path to having a good time.

This is the type of design that a good free-to-play game should pursue. One of the many complaints about free-to-play games is that the addition of purchases leads to manipulative game design. But manipulative design is not limited to attempting to extract money from wallets. As with Devil May Cry, it can be used to improve the game experience, and widen access to players with different play preferences. If you want to get technical about it, contemporary free-to-play experts would probably call Devil May Cry’s lava spider a retention system. The lingo might make you feel yucky, but the concept is sound: it’s a way to get more people to give the game a second or third chance, to identify what kind of game they want to play, and prepare them for the dramatically deeper content ahead.

There’s no question that the addition of real-money purchases changes the emotional tone of the game for some players. There’s no question that many of the mechanisms used by free games to make money could be considered manipulative. Certainly there are games that are designed without respect for their audience, but what of games that manipulate out of respect? But what if the purpose of that manipulation was to improve the fun factor? What if the purpose was to force the player to choose between a skill-based challenge or content tourism? What if we could use the emotional impact of a real-money purchase to manipulate some players into enjoying the game more? Traditional games do this all the time; should free-to-play games be any different?

We think that in-app purchases can be put to better use than just fishing for a small fraction of the audience that likes to spend big. We think they can be used as a way to increase the quality of the game, both for those who purchase things and for those who do not. In the next post I’ll write about how we’re trying to do that with Wind-up Knight 2.